Continuing Taia Global’s Spooks & Suits conference is a panel discussion I’ve been looking forward to for a while: “How much Leeway is there in the CFAA and International Law for Offensive Actions in Cyberspace.” Dr. Catherine Lotrionte is moderating, with Stewart Baker, Frank Cilluffo, and Marco Obiso comprising the panel. Unfortunately I had to walk from a panel titled “Taking the Fight to the Adversary”; it sounded like a good one.

Dr. Lotrionte opened, discussing the rules that currently exist impacting cyberspace. First we have international law, which of course was intended to apply to states, but (probably) also applies to non-state actors. In the area of use of force, the UN charter is obviously numero uno, specifically Article 2(4) (the prohibition on use of force). That principle is increasingly being applied to non-state actors, and this is relevant for private actors engaged in hackback. Very interesting point: Dr. Lotrionte said that the Tallinn Manual didn’t cover actions below the use of force threshold/espionage/cyberexploitation/intervention, BUT, there is a Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the way that will address hacks below the use of force threshold and that may be relevant to our private sector active defense discussions. Along those lines, Dr. Lotrionte believes that “somebody has to start dealing with [espionage] to decide what rules apply.” Finally, the Doctor noted there is uncertainty on whether international law applies to cyberspace: US says it does (see Harold Koh), Russia/China says it doesn’t, but even if it does, how does international law apply to non-state actors. The Dr. left it at that.

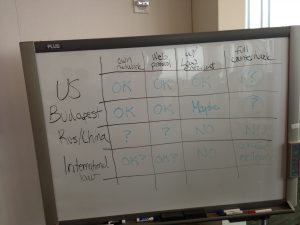

Stewart Baker then took the stage, referencing a whiteboard chart on when a person can place honeypots on your own network, place web protocol on your own network capable of dialing back, engage with law enforcement to hackback, and just full counterhack on your own. These categories were considered under US law, the Budapest convention, Russian/Chinese law, and international law. You can see that chart below, but I will be explaining the categories after the picture:

A few fun quotes from Mr. Baker: “Breaking people’s machines is silly, juvenile.” What we’re talking about is attribution and getting access to the adversary’s computer. “We’ll not defend our way out of this problem,” and we can’t solve the problem of street crime by telling people to buy better body armor. The key is to find ways to attribute cyber intrusions to hackers and punish them, and this is not a hopeless task. What can you do? Can you put stuff on your network and wait for it to be stolen? Put stuff on your network that uses web-protocol to call back? Can you do those things with law enforcement? Can you do a full counterhack?

Explanation of US Law: the gorilla in the room is the CFAA, or the unclear question of whether you’re changing/taking data without authorization. Mr. Baker believes that it’s legal under the CFAA if you put something (like a honeypot) on your own network. It’s more dangerous to put some sort of web protocol capable of “dialing back,” especially if that protocol involves some sort of injection, but still probably legal. Now to the good stuff. Mr. Baker believes that a full counterhack under the CFAA is arguably legal, but you would need an appetite for risk to actually engage it. Moreover, he believes that if a private entity does a full counterhack with law enforcement help/authorization, it’s fully legal under the CFAA. Note that “law enforcement authorization” would likely imply the full panoply of legal protections, including warrants, judicial process, etc. Ultimately, and very significantly, Mr. Baker believes that counterhacking will become popular with law enforcement help.

Regarding the Budapest Convention, Mr. Baker noted that the same people who came up with the CFAA wrote the Budapest Convention. Private sector counterhacking, with law enforcement, under international law (and the Budapest Convention, I guess), is questionable. A gentleman from the audience noted that Netherlands has a proposed law that would allow Dutch law enforcement to hack internationally. In this area, law enforcement is not able to operate with certainty.

Regarding Russia/China, something I didn’t know (via Mr. Baker): Russia will indict FBI agents who hack into computers of Russians and steal information.

On to international law. There is no IL regulation on intelligence gathering/cyberespionage; it’s a violation of host nation law, but not international law. Mr. Baker proposed a global counterhacking approach where private entities work with law enforcement authorities under a general understanding between the Budapest signatories. Alternatively, we could have intelligence agencies do what they do best and use any collected information to effectuate trade sanctions against certain parties.

The discussion moved to an argument over nature of trespassing/authorization under the CFAA. The argument was lively, and it highlighted just how ambiguous the CFAA’s language is. One gentleman from the audience noted that a deputy guarding a physical building can chase thieves off of company property; why not in cyber as well?

Marco Obiso made several interesting points. First, he noted the clear differences amongst the 190 members of the UN and the impact of those differences on any international cyber agreements. Indeed, some countries have no idea what we are talking about when discussing cyber, and these same countries are often hacker havens. If developed countries want to push forward on a successful global framework, they will need to get undeveloped countries to sign on. There was further discussion on the nature of the UN and the ITU. . . unfortunately I couldn’t get it all down.

Finally, Frank Cilluffo argued that you don’t deter cyber, you don’t deter weapons; you deter actors. I liked one of Mr. Cilluffo analogies: active defense is like a linebacker blitzing the quarterback. Finally, if we do project offensively, we need to make sure we are inoculated against anything we release.

Some random points:

- China wants a global treaty, panel largely agreed US doesn’t need it.

- The panel agreed that the US DOES NOT engage in IP theft/cyberexploitation (as opposed to cyberespionage), though other countries may not believe it.

- There was some discussion on amending the CFAA, possibly as a component of upcoming cyber legislation. Such an amendment could explicitly allow the private sector to hackback, or alternatively, create a civil right of litigation for those companies facing cyberexploitation. Another solution is to use trade sanctions.

*Disclaimer*

These blog posts are my informal summary of these speaker panels, so don’t take these as official quotes from the speakers. Also, I’m under the impression that Taia Global is not recording these discussions, so my intent here is to memorialize their content rather than steal any of Taia Global’s thunder. Again, all credit to the speakers and Taia Global.

This continues to be a wonderful event, by the way.

My thoughts

Like a sort of Stewart Baker-Orrin Kerr Volokh redo, the audience and panel couldn’t agreed on what “authorized” means under the CFAA. Why don’t we just cut the Gordian knot and rewrite the CFAA to explicitly allow private sector hackback under a strict deputization arrangement? Or rewrite the CFAA to make hackback explicitly illegal. Even if the CFAA authorization language prohibits hackback, I don’t think it’s necessarily illegal if a right of defense of property might apply. Remember, no court has held on this.

I also really liked Mr. Baker’s idea for a Budapest signatory regime where we enable hackback on the international stage. I previously suggested a similar arrangement amongst NATO members . . . essentially, get some like-minded states together and agree that justified private sector self-defense is not an illegal use of force/violation of the prohibition on intervention. Maybe a Cyber Montreux Document or a cyber version of the IMO’s recent regulation authorizing private ships to take self-defense measures against pirates. Whatever the case, even if we authorize some private sector active defense on a domestic level, we’ll have to clarify it on the international level.

1 Pingback